Link to installation images

Elizabeth Moran: Against The Best Possible Sources

Curated by Olivia Smith

September 6–December 20, 2019

Hawn Gallery / Hamon Arts Library at SMU Meadows School of the Arts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

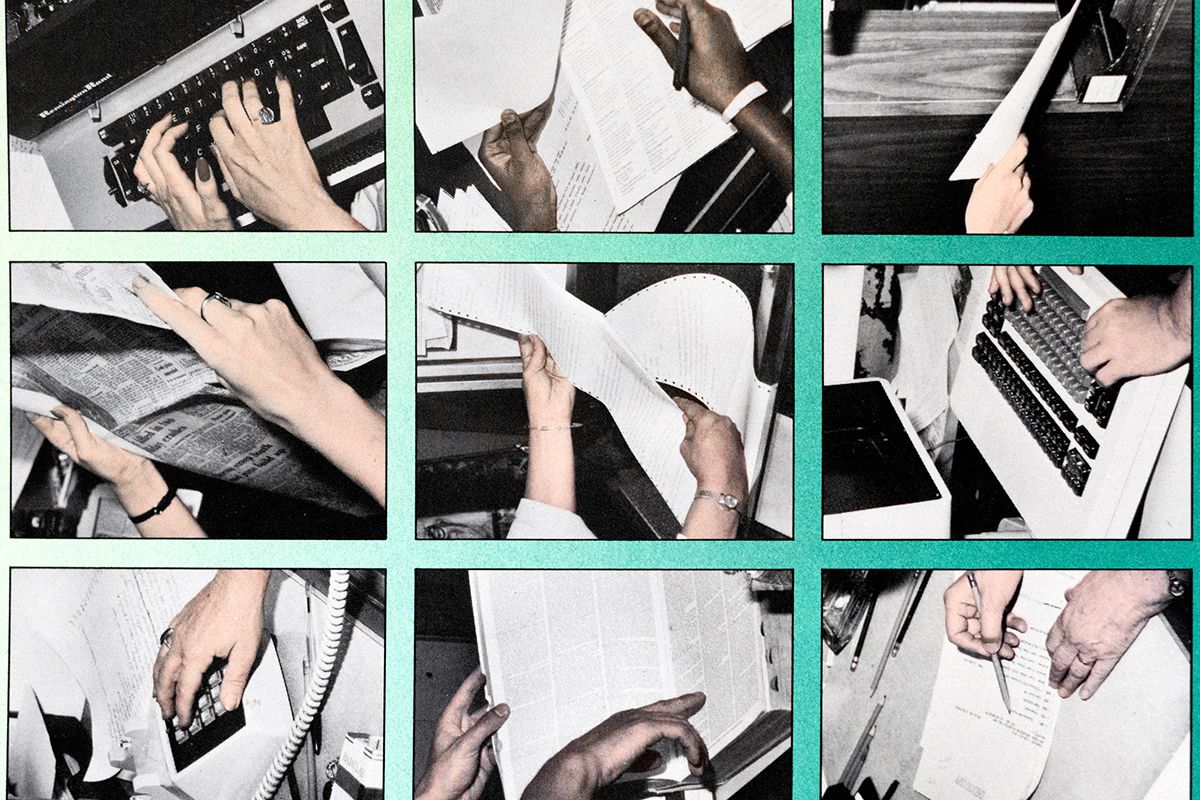

Against the Best Possible Sources is part of an ongoing project by Elizabeth Moran involving extensive research of the TIME, Inc. corporate archive and an investigation of the earliest history of the first professional journalistic fact-checkers, a role created by TIME in 1923 and held exclusively by women until 1971. Few first-person accounts of the women’s experiences remain. Instead, the majority of their stories are found only through internal correspondences with their male colleagues still preserved in the company’s archives: hand-drawn cartoons, scribbled notes, and reminiscences capture the prevailing sexism of the time—a sustained male gaze through which the women and their work was seen, recorded, and mythologized.

In this site specific installation, Moran recomposes these questionable, secondary sources creating a new narrative that is both unreliable but also the most comprehensive account of the first fact-checkers that exists today. Against the Best Possible Sources consists of decommissioned library shelves sourced from SMU’s Hamon Arts Library, decommissioned library books, dye-sublimation printed steel bookends, stamped photocopies created by TIME, Inc. archive librarians, and a decommissioned Kodak Carousel 860H slide projector with eighty 35mm slides. In her accompanying audio piece, Moran utilizes creative nonfiction strategies including a newly commissioned musical duet to unveil the simultaneous presence and absence of these women and their contribution to modern journalism.

Reacting against the sensationalized, tabloid journalism of the Progressive Era, TIME originally advertised their reporting as “written after the most exhaustive scrutiny of news-sources” with confirmed, reliable facts as its primary innovation and product. Indeed founders Henry Luce and Briton Hadden originally considered naming the weekly news magazine Facts. However this “exhaustive scrutiny” was considered women’s work from its inception: employment requirements found in early fact-checking manuals specified that checkers must be under age thirty, must be blonde, must wear stockings and specific gloves depending on the time of year, must wear hatpins under 6-inches in length and that checkers must maintain their “domestic list of chores.”

While female fact-checkers were considered subordinate to the male staff writers, the checkers had the power to kill any story that they could not verify—a decision that would impact a writer’s income. One such writer, Roger S. Hewlett, rewrote the lyrics to American composer Irving Berlin’s major Broadway hit, “You’re Just In Love,” and sarcastically serenaded the checkers whenever they would kill one of his stories. For this exhibition, Moran commissioned young Broadway singers to perform Hewlett’s rendition, “Checking Time (A duet in descant),” which flagrantly includes the refrain, “They’re not lies, they’re just not true.”

Nancy Ford was hired in early 1923 as the organization’s first fact-checker. As such, Ford laid the groundwork for fact-checking processes still in use to this day by supplying and verifying the facts for TIME, Inc.’s writers. The only three reference books available to her and her colleagues were The Bible, Homer’s Iliad, and Xenophon’s Anabasis. For any other references or research, the early checkers went to the New York Public Library, which they used as a second office. By 1929 the female employees began organizing their years of research for TIME into their own in-house library, nicknamed the Morgue. By the 1960s, the Morgue had grown to include 83,000 books and 500,000 folders of reference material and continued expanding through the 1990s when it was renamed the Time Warner Research Center. Over time, the primary sources used by the fact-checkers have been retired into storage or eliminated completely. Following a merger in 2001, AOL Time Warner announced the closing of the Research Center and laid-off its thirty-six full-time researchers. The archive is now housed within the New York Historical Society in Manhattan.

In this exhibition, Moran conflates this loss of primary sources with the untold stories and contributions of the early fact-checkers through photography, text, sound, and other forms of recorded documentation. The ten-minute audio narration by the artist is constructed from found texts sourced exclusively from the TIME, Inc. archive and published in this booklet as a visual collage. Presented in the installation as stereo sound, Moran has chosen to position male narration and supposedly objective information through the left speaker, while women’s subjective statements in the first person can be heard through the right speaker. The result, a ping-ponging chorus of anonymous voices all told and equalized through the artist’s own. Decommissioned library shelves found at SMU are presented as skeletal remains emptied of their contents. Scattered throughout the shelves are artist-made bookends rendered useless save for their surfaces, which display images of found artifacts and office materials entombed in TIME, Inc.’s archive. Only decommissioned library books of The Bible, Homer’s Iliad, and Xenophon’s Anabasis linger, replicating TIME’s first library now deemed unwanted.

The Kodak Carousel slide projector flickers in the back of the gallery briefly illuminating photographs, internal memos, records, and other ephemera which shed light on the original fact-checkers. The slide projector itself, first patented in 1965 and discontinued in 2004, presents a media technology that was both invented and subsequently discarded within the time period of Moran’s research. The projected images were made with Moran’s cell phone during her visits to the archive and were translated into slide film for this exhibition. This photo montage displays the employees and environment of TIME, Inc. and are not presented in chronological order. The artist’s hand can be seen arranging and proffering these documents—the limb of a disembodied researcher comingling with the unidentified individuals in the pictures. Visually presented in an analog format which exudes a credible formality, the eighty 35mm film slides—blasted by the light and heat of the mechanical operations—will degrade over time.

Through her own inquiry, Moran embodies the processes of these women by reperforming their meticulous labor, and her own subjectivity—her selection of texts, images, and choices in framing and cropping of photographs—becomes the buried content the viewer unearths. A swirling experience of theatrics, Moran’s installation moves in and out of various time periods like shadow play, sound and image bleeding together into an almost ungraspable abstraction. As one TIME, Inc. memo from 1967 states, “Without highly sophisticated methods of addressing stored data, we are lost.” Amid decommissioned objects and archaic technology, Moran positions her research as verifiable, interrogating the historical association between women’s work and fact-checking, while simultaneously examining the reliability of the information itself.

Artist Biography

Elizabeth Moran’s (b. 1984, Houston, TX) project-based practice examines the reliance on alleged objectivity within personal and societal systems of belief. Moran has received fellowships from the The San Francisco Foundation and the Tierney Family Foundation. Solo exhibitions include Cuchifritos Gallery, New York, NY; Black Crown Gallery, Oakland, California; and NYU's Gulf and Western Gallery, New York, NY. Her work has been included in group exhibitions at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, CA; Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California; Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, California; and Studio la Città, Verona, Italy. She has been an artist-in-residence at Vermont Studio Center, New York Art Residency and Studios (NARS) Foundation, Wassaic Project, Artists Alliance Inc’s LES Studio Program, and Rayko Photo Center. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, WIRED, VICE, and British Journal of Photography, among others. Moran holds an MFA + MA in Visual & Critical Studies from California College of the Arts and a BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. She lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

Curator Biography

Olivia Smith (b. 1988, Dallas, TX) received her BFA in 2011 from SMU Meadows School of the Arts in Studio Art, Art History, and English, with a concentration in Poetry. After concluding an internship at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, she moved to New York City in 2012. Smith is the co-founder and director of Magenta Plains, a contemporary art gallery opened in March 2016 and located in the Lower East Side of NYC. One of the core missions at the gallery is to bring greater attention to significant art and artists regardless of age or career and to present context and meaning for the development of new ideas as well as to preserve older generation artists' work. Among the thirty exhibitions to date at the gallery, Smith has organized critically acclaimed exhibitions with computer art pioneer Lillian Schwartz (b. 1927), minimalist painter Don Dudley (b. 1930), and avant-garde legend Barbara Ess (b. 1948). Exhibitions at Magenta Plains have been reviewed in The New York Times, Artforum, The New Yorker, Art In America, The Nation, Forbes, The New York Observer, Frieze, The Brooklyn Rail, Artnews, Artinfo, Artnet, and more.

Monday, December 7, 2020 at 7:59PM

Monday, December 7, 2020 at 7:59PM  oliviasmith | Comments Off |

oliviasmith | Comments Off |